More than just a language, Hebrew is a people, a history, and a culture woven through time. It reflects three thousand years of religious, intellectual, and cultural evolution which have shaped the way Hebrew is written, spoken, and understood in modern day.

From sacred scrolls to modern media, Hebrew has undergone several significant historical stages that have shaped the language we know today. So, let’s explore five key eras that define this extraordinary linguistic legacy: Biblical Hebrew, Inter-Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew, Mishnaic Hebrew, Medieval Hebrew, and Modern Hebrew.

Biblical Hebrew

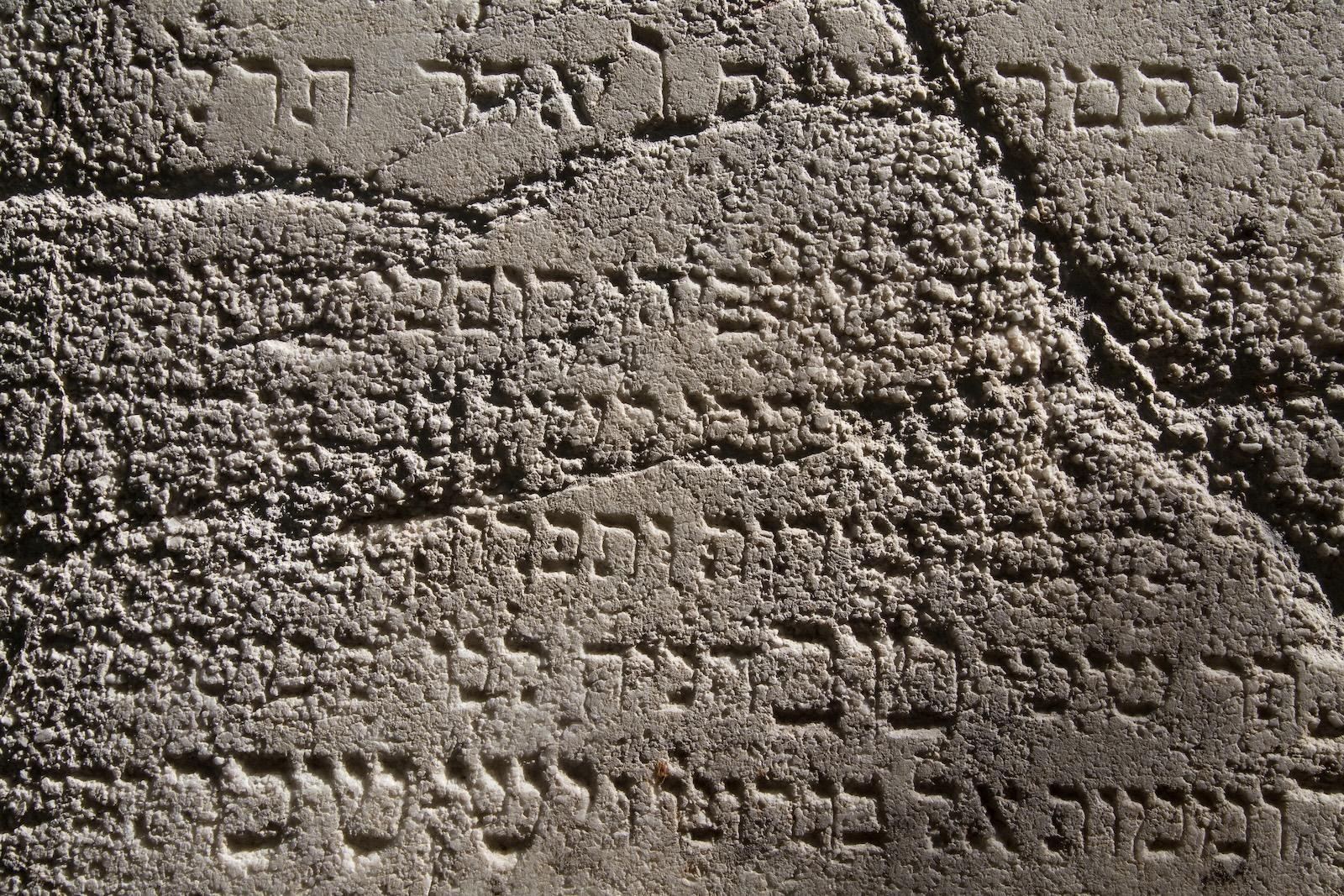

As early as 10th century BCE, inscriptions offer physical testimony to Hebrew’s early use. A pottery shard recently discovered in Emek Ha’Ela may date as far back as King David’s reign. Other important inscriptions from the First Temple Period shape our understanding of the earliest era of Hebrew, known as Biblical Hebrew.

The era of Biblical Hebrew is said to have three distinct periods that span through time:

- Archaic Biblical Hebrew – Represented by some of the poems in the Pentateuch and the Prophets

- Standard Biblical Hebrew – Found in the Biblical prose from Genesis through Second Kings

- Late Biblical Hebrew – As seen in post-exilic books like Ezra, Nehemiah, Daniel, and Chronicles

This period features a rich verbal system with seven common verb stems that can be used to convey concepts like nuances of action, passivity, reflexivity, reciprocity, and intensity, as well as a complex system of denoting subtle indications of time and aspect.

Loanwords in Biblical Hebrew provide insights into ancient Jewish life. While native terms reflect agriculture and daily living, technical and commercial vocabulary often come from foreign loan words — largely derived from Akkadian, Aramaic, and other languages via trade routes. For example, the names of Hebrew months we know today come from Akkadian while the names of months in Standard Biblical Hebrew reflect the ancient Canaanite calendar.

In Second Temple times, Hebrew adopted the Aramaic alphabet, sparking a widespread and lasting mark on the Hebrew language that is so seamless it’s nearly impossible to detect! The two languages became symbiotic during the nearly one thousand years before Hebrew ceased being a spoken language at the end of the second century CE.

Inter-Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew

Since all sources from this time period are written or literary, scholars know little about the actual spoken language of this period. However, several remarkable documents from this time shed light on the written language of the time and how it has shaped Hebrew through time:

- Cairo Geniza: Discovered in Egypt in the 19th century, this collection of important documents revolutionized the study of Jewish history and language. Among its treasures was a Hebrew version of the Book of Ben Sira, long thought lost. Additional Hebrew fragments of Ben Sira, dating to around 125–100 BCE and discovered at Masada, also provide a window into the history of the Hebrew language and the intertestamental literature of the time. Ben Sira sought to imitate the grammar and style of Biblical Hebrew, drawing heavily on the Hebrew Bible, yet it was also influenced by contemporary spoken languages such as Mishnaic Hebrew and Aramaic, as well as other foreign sources.

- Dead Sea Scrolls: In 1947, 2,000-year-old texts originally part of a library of a Jewish sect were discovered in caves in Qumran. While the scrolls demonstrate the influence of Aramaic on the language, they most notably reveal a stark lack of words adapted from additional languages such as Greek and Latin. One theory suggests that there was a conscious effort by the writers to reject the foreign influence on their sacred language. Instead, a number of terms appear to have been translated from Latin. The writers also took Biblical Hebrew roots or words with lost or unknown meanings and gave them new meaning. As a result of the scrolls, there are several words whose meanings are only now more fully understood to scholars of Biblical Hebrew.

After the fall of the Second Temple and the downfall of Biblical Hebrew, Mishnaic Hebrew rose to fill the gap. The Bar-Kokhba letters written during the Second Jewish Revolt (132-135 CE) revealed that this form of Hebrew was the spoken language of the region. After the Second Jewish Wars, most native speakers of the tongue were killed, and Mishnaic Hebrew remained as a literary language.

Mishnaic Hebrew can be broken down into two key strata:

- MH1: The older linguistic stratum in the Talmudim and the spoken language of the Tannaim

- MH2: No longer spoken naturally but used as a literary language and religious discourse in the Talmudim

Mishnaic Hebrew vocabulary evolved from semantic and structural changes to Biblical words, including expanded meaning, along with the inclusion of foreign words. Transliterations like the Secunda (from Origen’s Hexapla, an edition of the Bible from the third century CE) contributed to our understanding of Hebrew pronunciation of the time. Another is the work of St. Jerome who preserved several words of Mishnaic Hebrew in his writings from the end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth century CE.

Though no longer widely spoken after the 5th century CE, Hebrew was thought to be spoken among Jews traveling or migrating, as a spoken language in the Holy Land, and perhaps even as an instructional language of Jewish schools in Muslim countries and in Amsterdam.

Nonetheless, Hebrew thrived as a literary language until its modern revival as a spoken language and continued to evolve with foreign influences. Since Jews were widely dispersed during this time, Hebrew borrowed from, and was borrowed by, foreign languages — in particular Arabic was influential in the language of literature and sciences. Major developments in this era include:

- New Jewish languages which arose as the result of contact between different spoken vernaculars and Hebrew, such as Yiddish (German and Hebrew), Ladino (Spanish and Hebrew), and Judaeo-Arabic (Arabic and Hebrew)

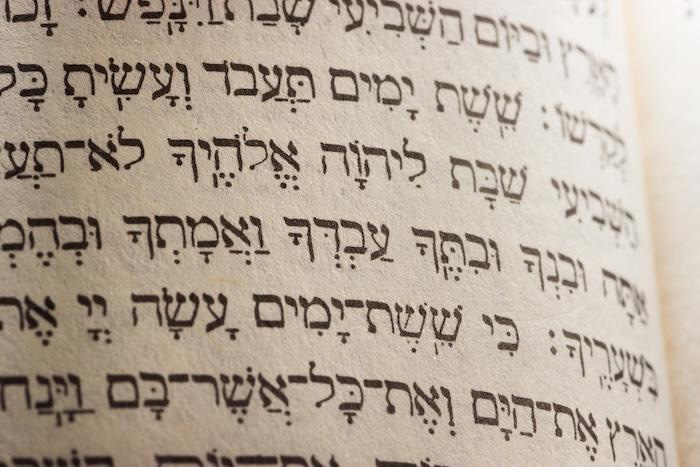

- Vocalization systems, such as the invention of vocalized vowel signs, the rise of Hebrew grammar and lexicography, and the Masoretic system which standardized the Biblical pronunciation — enabling every literate Jew to read the Bible

- A new genre of religious poetry, Piyyut, emerged which used innovative linguistic tactics and, controversially, drew on Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew

- A new branch of secular poetry also emerged, written with a freer hand, leading to new verbs and nouns created from existing Hebrew roots

- The advent of Hebrew linguistics by Karaite scholars and a golden age in linguistic research by Jews in 10th-13th century Spain, greatly influenced by Arabic grammar

- Thousands of new terms and syntactical forms were brought into the language through Hebrew translations of Arabic works during the Islamic world’s golden age of enlightenment and scientific thinking

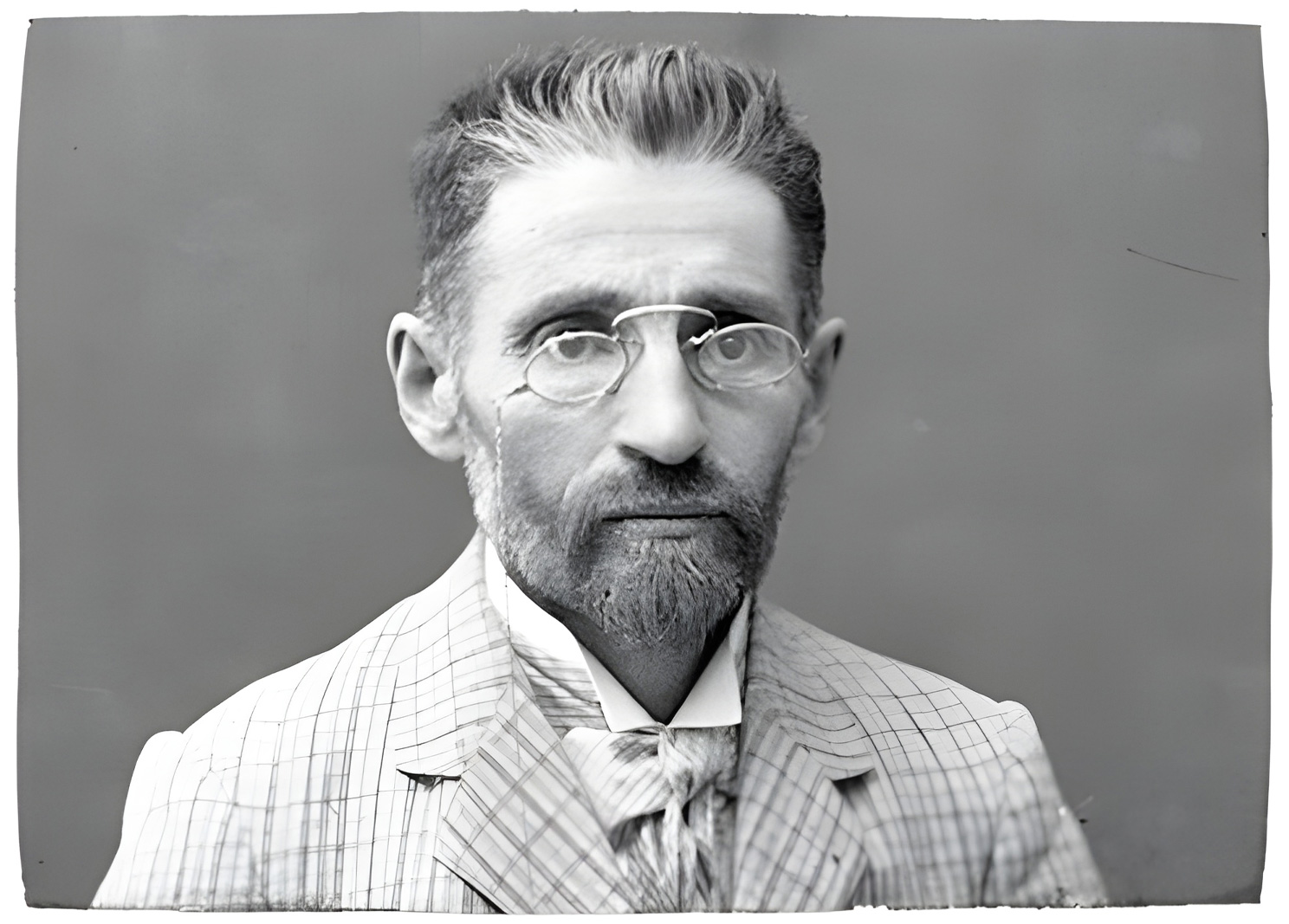

In the 19th century, Mendele Mokher Sefarim (also known as Sholem Yakov Abramovich) transformed Hebrew into a functional literary language suitable for secular topics, drawing on sources like Mishnaic Hebrew, Medieval Hebrew, Aramaic, and rabbinic texts. Often called the Creator of Modern Hebrew, he is also considered the father of two literary languages, Hebrew and Yiddish, which he brought into more academic usages.

While his influence was pivotal, Mendele had no intent to revive Hebrew as a spoken language. Instead, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, often called the Father of Modern Hebrew, led the charge to resurrect Hebrew as the everyday language of a modern nation. He went on to establish a Jerusalem-based Literature Committee in 1889 which, through many iterations, eventually sparked the creation of the Academy of the Hebrew Language.

Hebrew’s journey is far from over. While each era has added new dimensions, vocabulary, and vitality, the language continues to grow and adapt — with modern use from Hebrew speakers and the tireless work of the Academy. You can explore how ancient roots continue to shape contemporary expression and discover the living language of Hebrew through the Academy’s Historical Dictionary Project and ongoing terminology innovation.

As Friends of the Academy of the Hebrew Language, we honor the rich heritage of the Hebrew language by supporting the Academy of the Hebrew Language’s research, education, and cultural engagement. To join us in this important work, become a friend today!

Read this blog to find out how The Academy of the Hebrew Language approaches the important task of creating guidelines for Hebrew transliteration.

From the history of the Hebrew language to the Hebrew revival, let’s explore what exactly makes Hebrew so unique amongst the world’s languages.

Let’s take a deeper look at the life of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and his integral role in the revival of the Hebrew language to that we see today.

Learn the fascinating story of Israeli Sign Language, its inception, its ongoing development and its place in inclusive education.