How the Academy of the Hebrew Language Approaches Transliteration

Hebrew is a rich, vibrant, and important language. Moreover, it is a window into the life, culture, and history of all who speak it. This is what makes it so crucial to preserve and protect the essence of the language, its meaning, and its place at the forefront of the Hebrew speaking world. This is an integral part of the Academy of the Hebrew Language.

One way the Academy begins to fill this tall order is by providing clear, carefully considered rules for Hebrew transliteration, the process of reproducing the sounds of words from one language using the letters of another. Their careful process effectively offers people from around the world the ability to recognize, use, and appreciate Hebrew words and concepts without knowledge of Hebrew characters.

Let’s dive deeper into the basics and how the Academy approaches the important task of creating guidelines for Hebrew transliteration.

What Is the Purpose of Transliteration?

In addition to its central role in bridging linguistic and cultural gaps, the goal of transliteration is not to translate meaning, but to give readers of another language a way to pronounce Hebrew words as accurately as possible. In official and public settings, inconsistent or unclear transliteration can lead to confusion, mispronunciation, and the loss of important linguistic and cultural information.

To prevent this, the Academy created a standardized system for transliteration. To ensure widespread understanding and protection of the Hebrew language, this system is used consistently in government documents, signage, academic writing, and more.

How do the Academy’s Hebrew Transliteration Rules Work?

Following consistent, readable, and phonetically accurate standards, the Academy’s Hebrew transliteration guidelines aim to reflect the pronunciation of the word, not necessarily its spelling in the source language. These rules maintain accuracy across mediums, protecting the sanctity of Hebrew while allowing non-Hebrew speakers to understand and express themselves in a greater variety of contexts.

The Academy’s transliteration rules govern both the representation of the modern Hebrew language in Latin characters and the representation of other languages in Hebrew characters. Let’s go over each of these methods in more detail:

Transliterating Modern Hebrew into Latin Characters

First approved in 1957, the Academy’s rules for transliterating Modern Hebrew into Latin characters offers guidelines of simple transliteration for popular use in things like ads and street signs. It also offers modifications to make when more precise transliteration is needed for complex use cases, such as on a title page or in a catalog.

Simple transliteration minimizes the use of diacritical marks and allows a pair of Latin characters, such as sh or kh, to represent a single Hebrew consonant. In contrast, for precise transliteration, the Latin representation of a Hebrew consonant never exceeds one character and in some cases requires a special diacritical mark.

In response to popular demand, the Academy has revisited and revised their simple transliteration rules a few times to simplify it further and more closely align with contemporary Hebrew pronunciation.

Transliterating Foreign Languages into Hebrew Characters

The rules for transliterating foreign languages into Hebrew characters apply specifically to words that are not part of Hebrew, such as names of people and places. For this, the Academy has adopted two sets of rules, one for Arabic and another for non-Semitic languages. Both cases aim to reflect the pronunciation in Hebrew.

To transliterate Arabic into Hebrew for academic purposes, certain modifications apply that bring the Hebrew spelling more closely in line with written Classical Arabic. For foreign words that Hebrew has adopted and integrated into the language, slightly different rules apply. Much like with transliteration into Latin, the rules have also undergone revisions over the years.

To learn more about the academy’s specific transliteration rules, you can explore the official Hebrew transliteration rules online, or order a print copy.

Transliteration makes the beauty of the Hebrew language accessible to a wider audience, promoting greater global appreciation and understanding. Those who do not speak Hebrew, or who are in the process of learning, can understand and approximate the pronunciation of Hebrew words, creating an important cultural exchange that otherwise would be much more difficult.

This practice is also key to maintaining consistency of words and preserving the identity of different words, names, and concepts across texts in different languages such as passports, maps, signs, websites, academic publications, databases and more.

With Hebrew increasingly integrated into global communication, clear and consistent transliteration is essential. The Academy’s approach to transliteration continues to evolve alongside the Hebrew language. As Hebrew grows in global usage, from Israeli start-ups to Jewish communities around the world, so too must the tools that help it cross linguistic borders.

By maintaining and refining its transliteration system, the Academy ensures that Hebrew remains not only relevant but reachable; connecting people, identities, and cultures through common aspects of language.

At Friends of the Academy of the Hebrew Language, we support the Academy’s work protecting and preserving the Hebrew language through their tireless research, education, and cultural engagement efforts. We invite you to join us by becoming a friend today!

From the history of the Hebrew language to the Hebrew revival, let’s explore what exactly makes Hebrew so unique amongst the world’s languages.

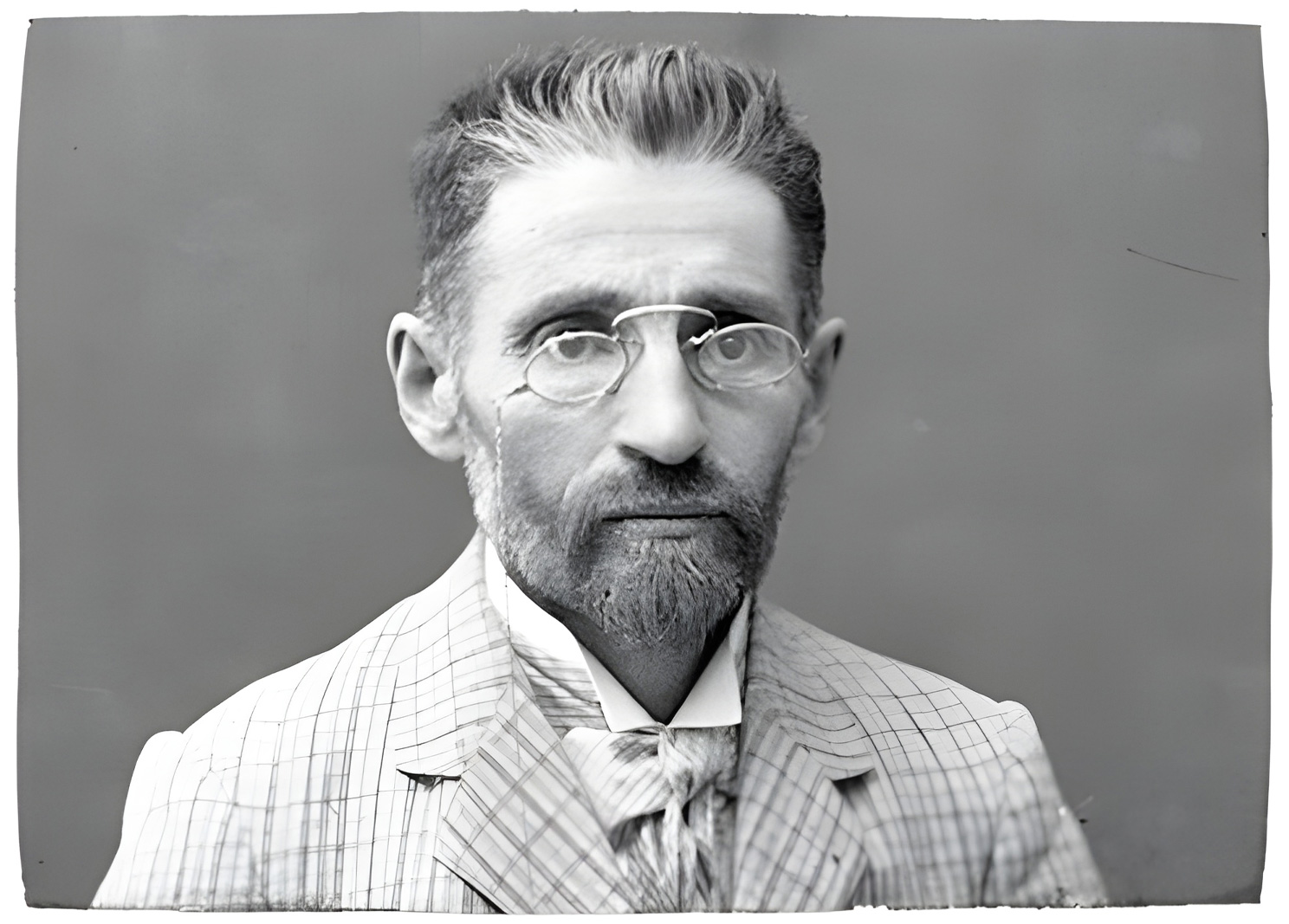

Let’s take a deeper look at the life of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and his integral role in the revival of the Hebrew language to that we see today.

The history of the Hebrew language is rich, beautiful, and complex. To learn more, read our Hebrew history timeline: Hebrew through the ages!

Learn the fascinating story of Israeli Sign Language, its inception, its ongoing development and its place in inclusive education.